Rooted in Generations

The origins of Gano lentil stew are planted deep in the soil of rural life. Long before it became tied to cultural pride or culinary revival, it was simply what people had and what they could make work. Farmers and herders, working sunup to sundown, needed food that was filling, simple to prepare, and made from what was already on hand. Lentils fit the bill: hardy, protein rich, and easy to store through dry or lean months.

This wasn’t a dish whipped up on a whim. It came from rhythm. Villages timed their cooking around the harvest cycles lentils, onions, garlic, and herbs pulled right from the field or traded at small markets. The stew was often simmered in large clay pots over wood fires, enough for families and neighbors alike. It was efficient, nourishing, and endlessly adaptable. No carrots this season? Use wild greens or dried squash. Out of oil? Crush sunflower seeds into paste.

Over time, this spirit of making do shaped the foundation of Gano’s food identity. The stew wasn’t just hearty. It was a reflection of resilience: cooking guided by what the land gave, seasoned by habit, necessity, and slow earned wisdom.

More than Just a Meal

In Gano, lentil stew isn’t simply sustenance it’s a nourishing cornerstone of community life and cultural continuity. Through generations, this humble dish has been woven into the very fabric of social and spiritual events.

A Centerpiece at Gatherings

Lentil stew often takes center stage at family celebrations, seasonal festivals, and life milestones. Whether honoring a birth, a wedding, or a homecoming, the stew offers more than just food:

It symbolizes warmth, unity, and shared abundance

Guests often contribute ingredients, reaffirming mutual care

Shared preparation and serving reinforce family bonds

Nourishment During Rituals and Fasting

Beyond celebration, lentil stew plays a meaningful role in periods of spiritual reflection. During fasting seasons and religious observances, the high protein, plant based dish becomes essential:

It fulfills dietary restrictions while still being satisfying

Lightweight yet filling, ideal for day end meals after fasting

Seen as a humble food that aligns with spiritual discipline

Recipes as Oral History

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of Gano lentil stew is how it’s passed down. Recipes aren’t just written down they are told, shown, and lived:

Mothers teach daughters through cooking side by side

Variations in spice or method reflect regional identity and family lore

Each version carries stories of migration, celebration, and endurance

In every way, lentil stew in Gano is a living tradition, embodying nourishment for both body and heritage.

Regional Twists That Tell a Story

Gano lentil stew may seem humble at a glance, but its variations offer a quiet map of the region’s history. Step into one village, and you’ll taste cardamom and dried lime aromas tracing back to ancient coastal trade. In another, it’s rosemary and fermented garlic, picked up from mountain routes that once carried both sheep and song. The core ingredients lentils, onions, a modest oil stay the same. But the spices speak volumes.

Each province has its fingerprint. In the north, cooks drop in tart sumac or woodland herbs. Along the river belts, a smoky paprika makes its appearance possibly an influence from passing settlers generations ago. Even cooking styles shift. Some simmer the stew low and slow over ground stone hearths, letting flavors deepen for hours. Others flash boil for speed, proof of busier urban rhythms creeping in.

The stew’s journey mirrors larger movements trading caravans, seasonal migrations, families pushed by drought or drawn by work. Over time, the pot absorbed pieces of it all. What lands on the plate isn’t just food. It’s a record. A blend of what’s local, what wandered in, and what stayed because it worked.

Tied to the Land, Tied to the People

Lentils weren’t just a crop in Gano they were survival. Grown in tough soil with minimal water, they delivered steady nutrition where little else could thrive. Through droughts, trade blockades, even war, lentils stayed. They stored well, cooked fast, and didn’t demand much. That practicality made them essential. Not flashy, but always there.

Gano lentil stew, born from this rooted necessity, holds more than protein. What’s packed in every bowl mirrors the region’s values: simplicity, resilience, and the sense that strength comes from feeding others. The dish isn’t dressing something up it’s showing things as they are. You take what the land gives. You make it matter. And you share it.

In Gano kitchens, the stew isn’t served with ceremony. It’s served with intent. That’s what makes it real.

Pairing Tradition: The Flatbread Connection

You’ll rarely find a bowl of Gano lentil stew without a side of its signature flatbread. This isn’t just habit it’s heritage. The bread, baked daily in clay ovens or iron pans, does more than mop up the stew. It completes it. Texture meets texture. Grain meets pulse. The pairing wasn’t born in restaurants. It came from home kitchens, from practicality, and from centuries of eating with hands, around shared plates.

The bread itself is a cultural touchstone. Made from hardy flours like barley or millet, it reflects the same survival instincts and resourcefulness as the stew. In many homes, the act of breaking flatbread is a ritual in itself one that marks everything from morning meals to holy days. Stew and flatbread together are more than food. They’re rhythm. They’re routine. And they carry the quiet weight of ancestry.

For more on how the flatbread became a symbol in its own right, explore Gano Flatbread Symbolism.

Resurgence in the Modern Kitchen

Across test kitchens and open air markets, a quiet revival is underway. Young Gano chefs, many trained abroad, are bringing back their grandmothers’ lentil stew recipes with just enough restraint to let the past speak. They’re not reinventing the wheel. They’re refining it: using heirloom lentils, grinding spices by hand, and serving the stew in clay bowls that nod to its rustic roots.

Food historians are getting involved too. Documentaries now trace the dish’s journey from subsistence to symbol. Academic projects archive regional variations, preserving the oral threads of recipe lines that were once passed ear to ear.

At cultural fairs, the scent of slow simmered lentils draws in curious crowds. Farm to table restaurants spotlight the stew’s honest simplicity alongside seasonal greens and fresh flatbread. It’s not flashy but that’s the point. The dish carries calm, not noise. It doesn’t demand attention; it earns it.

In a world chasing the next new thing, Gano lentil stew is a quiet ambassador. It tells a story without needing to speak loudly. And in that silence, it reconnects people to land, to family, to history.

Carried Forward by Every Bowl

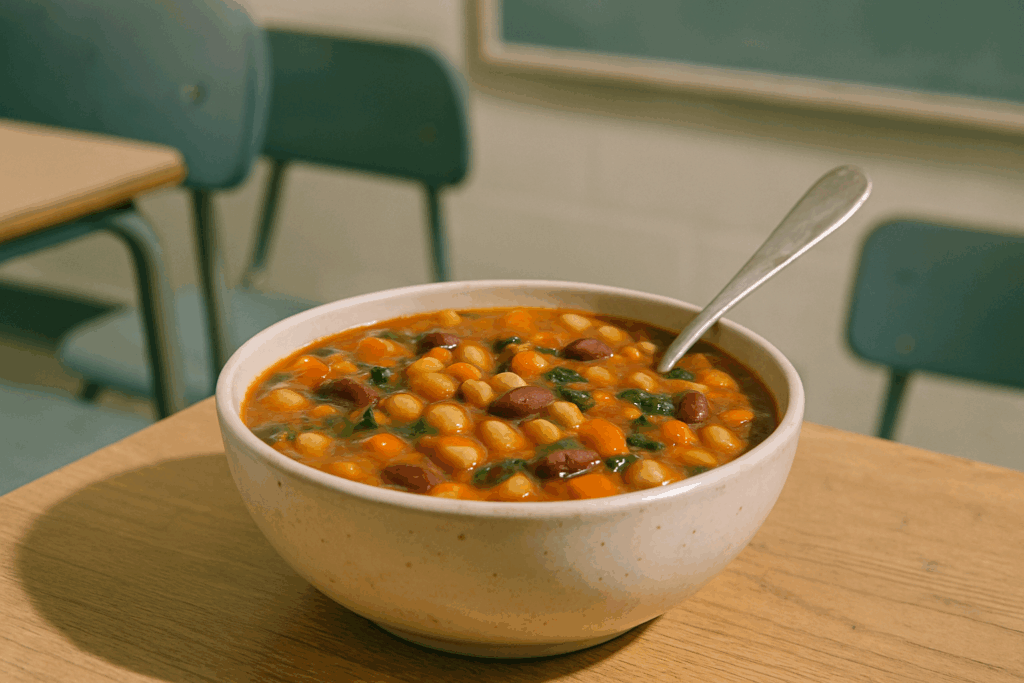

Gano lentil stew isn’t just food it’s memory made edible. At first glance, a simple bowl of lentils, herbs, and root vegetables doesn’t seem like much. But in Gano, it’s a symbol. A throughline from ancestors who made do with what they had, and made it well. The dish is woven into the fabric of national identity not through pomp, but by enduring through generations of quiet repetition shared recipes, shared meals, shared lives.

Its power lies in its simplicity. No exotic imports or expensive ingredients. Just things grown close to home, cooked slow, served warm. That steadiness is what gives the stew its strength. It feeds more than the body; it grounds people in something lasting. Everyone remembers a specific pot at a wedding, during a hard winter, or just an everyday meal with someone who’s now gone. That emotional texture can’t be replicated easily and frankly, it shouldn’t be.

Now, with globalization reshaping how people eat and live, there’s a conscious effort in Gano to preserve this culinary heirloom. Cultural groups are hosting village based recipe circles. Schools include it in nutrition history lessons. Even some modern chefs are bringing old world versions back onto menus, without upscale dilution. The goal isn’t to make it trendy. The goal is to keep it alive.

In Gano, it’s understood: you don’t protect the stew because it’s rare. You protect it because it’s yours.